The use of animals in scientific research and testing has long been a contentious issue, sparking debates on ethical, scientific, and societal grounds. Despite over a century of activism and the development of numerous alternatives, vivisection remains a prevalent practice worldwide. In this article, biologist Jordi Casamitjana delves into the current state of alternatives to animal experiments and animal testing, shedding light on the efforts to replace these practices with more humane and scientifically advanced methods. He also introduces Herbie’s Law, a groundbreaking initiative by the UK anti-vivisection movement aimed at setting a definitive end date for animal experiments.

Casamitjana begins by reflecting on the historical roots of the anti-vivisection movement, illustrated by his visits to the statue of the “brown dog” in Battersea Park, a poignant reminder of the early 20th-century controversies surrounding vivisection. This movement, led by pioneers like Dr. Anna Kingsford and Frances Power Cobbe, has evolved over the decades but continues to face significant challenges. Despite advancements in science and technology, the number of animals used in experiments has only grown, with millions suffering annually in laboratories around the world.

The article provides a comprehensive overview of the various types of animal experiments and their ethical implications, highlighting the stark reality that many of these tests are not only cruel but also scientifically flawed. Casamitjana argues that non-human animals are poor models for human biology, leading to a high failure rate in translating animal research findings to human clinical outcomes. This methodological flaw underscores the urgent need for more reliable and humane alternatives.

Casamitjana then explores the promising landscape of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), which include human cell cultures, organs-on-chips, and computer-based technologies. These innovative methods offer the potential to revolutionize biomedical research by providing human-relevant results without the ethical and scientific drawbacks of animal testing. He details the advancements in these fields, from the development of 3D human cell models to the use of AI in drug design, showcasing their effectiveness and potential to replace animal experiments entirely.

The article also highlights significant international progress in reducing animal testing, with legislative changes in countries like the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. These efforts reflect a growing recognition of the need to transition to more ethical and scientifically sound research practices.

In the UK, the anti-vivisection movement is gaining momentum with the introduction of Herbie’s Law. Named after a beagle spared from research, this proposed legislation aims to set 2035 as the target year for the complete replacement of animal experiments. The law outlines a strategic plan involving government action, financial incentives for developing human-specific technologies, and support for scientists transitioning away from animal use.

Casamitjana concludes by emphasizing the importance of abolitionist approaches, like those advocated by Animal Free Research UK, which focus solely on the replacement of animal experiments rather than their reduction or refinement. Herbie’s Law represents a bold and necessary step towards a future where scientific progress is achieved without animal suffering, aligning with the ethical and scientific advancements of our time.

The use of animals in scientific research and testing has long been a contentious issue, sparking debates on ethical, scientific, and societal grounds. Despite over a century of activism and the development of numerous alternatives, vivisection remains a prevalent practice worldwide. In this article, biologist Jordi Casamitjana delves into the current state of alternatives to animal experiments and animal testing, shedding light on the efforts to replace these practices with more humane and scientifically advanced methods. He also introduces Herbie’s Law, a groundbreaking initiative by the UK anti-vivisection movement aimed at setting a definitive end date for animal experiments.

Casamitjana begins by reflecting on the historical roots of the anti-vivisection movement, illustrated by his visits to the statue of the “brown dog” in Battersea Park, a poignant reminder of the early 20th-century controversies surrounding vivisection. This movement, led by pioneers like Dr. Anna Kingsford and Frances Power Cobbe, has evolved over the decades but continues to face significant challenges. Despite advancements in science and technology, the number of animals used in experiments has only grown, with millions suffering annually in laboratories around the world.

The article provides a comprehensive overview of the various types of animal experiments and their ethical implications, highlighting the stark reality that many of these tests are not only cruel but also scientifically flawed. Casamitjana argues that non-human animals are poor models for human biology, leading to a high failure rate in translating animal research findings to human clinical outcomes. This methodological flaw underscores the urgent need for more reliable and humane alternatives.

Casamitjana then explores the promising landscape of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), which include human cell cultures, organs-on-chips, and computer-based technologies. These innovative methods offer the potential to revolutionize biomedical research by providing human-relevant results without the ethical and scientific drawbacks of animal testing. He details the advancements in these fields, from the development of 3D human cell models to the use of AI in drug design, showcasing their effectiveness and potential to replace animal experiments entirely.

The article also highlights significant international progress in reducing animal testing, with legislative changes in countries like the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. These efforts reflect a growing recognition of the need to transition to more ethical and scientifically sound research practices.

In the UK, the anti-vivisection movement is gaining momentum with the introduction of Herbie’s Law. Named after a beagle spared from research, this proposed legislation aims to set 2035 as the target year for the complete replacement of animal experiments. The law outlines a strategic plan involving government action, financial incentives for developing human-specific technologies, and support for scientists transitioning away from animal use.

Casamitjana concludes by emphasizing the importance of abolitionist approaches, like those advocated by Animal Free Research UK, which focus solely on the replacement of animal experiments rather than their reduction or refinement. Herbie’s Law represents a bold and necessary step towards a future where scientific progress is achieved without animal suffering, aligning with the ethical and scientific advancements of our time.

Biologist Jordi Casamitjana looks at the current alternatives to animal experiments and animal testing, and at Herbie’s Law, the next ambitious project of the UK anti-vivisection movement

I like to visit him from time to time.

Hidden in a corner of Battersea Park in South London, there is a statue of the “brown dog” I like to pay my respects to now and then. The statue is a memorial of a brown terrier dog who died in pain during vivisection performed on him before an audience of 60 medical students in 1903, and who was the centre of a big controversy, as Swedish activists had infiltrated the University of London medical lectures to expose what they called illegal vivisection acts. The memorial, unveiled in 1907, also caused controversy, as medical students at London’s teaching hospitals were enraged, causing riots. The monument was eventually removed, and a new memorial was built in 1985 to honour not just the dog, but the first monument that was so successful in raising awareness of the cruelty of animal experiments.

As you can see, the anti-vivisection movement is one of the oldest subgroups within the broader animal protection movement. Pioneers in the 19th century, such as Dr Anna Kingsford, Annie Besant, and Frances Power Cobbe (who founded the British Union Against Vivisection by uniting five different anti-vivisection societies) led the movement in the UK at the same time suffragettes were fighting for women’s rights.

Over 100 years have passed, but vivisection continues to be practised in many countries, including the UK, which remains one of the countries where animals suffer at the hands of scientists. In 2005, it was estimated that more than 115 million animals were used worldwide in experimentation or to supply the biomedical industry. Ten years later, the number grew to an estimated 192.1 million, and now it is likely to have passed the 200 million mark. The Humane Society International estimates that 10,000 animals are killed for every new pesticide chemical tested. The number of animals used in experimental research in the EU is estimated to be 9.4m, with 3.88m of these being mice. According to the latest figures from the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA), more than 90,000 non-human animals were used for testing in Irish laboratories in 2022.

In Great Britain, the number of mice used in 2020 was 933,000. The total number of procedures on animals conducted in the UK in 2022 was 2,761,204, of which 71.39% involved mice, 13.44% fishes, 6.73% rats, and 4.93% birds. From all these experiments, 54,696 were assessed as severe, and 15,000 experiments were carried out on specially protected species (cats, dogs, horses, and monkeys).

The animals in experimental research (sometimes called “lab animals”) usually come from breeding centres (some of which keep specific domestic breeds of mice and rats), which are known as class-A dealers, while class-B dealers are the brokers who acquire the animals from miscellaneous sources (like auctions and animal shelters). Therefore, the suffering of being experimented upon should be added to the suffering of being bred in overcrowded centres and being kept in captivity.

Many alternatives to animal tests and research have already been developed, but politicians, academic institutions, and the pharmaceutical industry remain resistant to applying them to replace the use of animals. This article is an overview of where we are now with these replacements and what is next for the UK anti-vivisection movement.

What is Vivisection?

The vivisection industry is mainly composed of two types of activities, animal testing and animal experiments. An animal test is any safety test of a product, drug, ingredient, or procedure done to benefit humans in which live animals are forced to undergo something likely to cause them pain, suffering, distress, or lasting harm. This type is normally driven by commercial industries (such as the pharmaceutical, biomedical, or cosmetics industries).

Animal experiments are any scientific experiment using captive animals to further medical, biological, military, physics, or engineering research, in which the animals are also forced to undergo something likely to cause them pain, suffering, distress, or lasting harm to investigate a human-related issue. This is normally driven by academics such as medical scientists, biologists, physiologists, or psychologists. A scientific experiment is a procedure scientists undertake to make a discovery, test a hypothesis, or demonstrate a known fact, which involves a controlled intervention and an analysis of the reaction of the experimental subjects to such intervention (as opposed to scientific observations that do not involve any intervention and rather observe the subjects behaving naturally).

Sometimes the term “animal research” is used as a synonym for both animal tests and animal experiments, but this could be a bit misleading as other types of researchers, such as zoologists, ethologists, or marine biologists may conduct non-intrusive research with wild animals that only involves observation or collecting faeces or urine in the wild, and such research is normally ethical, and should not be lumped in with vivisection, which is never ethical. The term “animal-free research” is always used as the opposite of animal experiments or tests. Alternatively, the term “animal testing” is used to mean both the testing and the scientific experiments made with animals (you can always look at a scientific experiment as a “test” of a hypothesis too).

The term vivisection (literally meaning “dissecting alive”) can also be used, but originally, this term only included the dissection or operation of live animals for anatomical research and medical teaching, but not all experiments that cause suffering involve the cutting of animals anymore, so this term is regarded by some as too narrow and antiquated for common use. However, I use it quite often because I think it is a useful term firmly linked with the social movement against animal experiments, and its connection with “cutting” reminds us more of the animals suffering than any more ambiguous or euphemistic term.

Animal tests and experiments include injecting or force-feeding animals with potentially harmful substances, surgically removing animals’ organs or tissues to deliberately cause damage, forcing animals to inhale toxic gases, subjecting animals to frightening situations to create anxiety and depression, hurting animals with weapons, or testing the safety of vehicles by trapping animals inside them while operating them to their limits.

Some experiments and tests are designed to include the death of these animals. For example, tests for Botox, vaccines, and some chemicals are variations of the Lethal Dose 50 test in which 50% of the animals die or are killed just before the point of death, to assess which is the lethal dose of the substance tested.

Animal Experiments Don’t Work

The animal experiments and tests that are part of the vivisection industry are normally aimed at solving a human problem. They are either used to understand how humans’ biology and physiology work, and how human diseases can be combated, or are used to test how humans would react to particular substances or procedures. As humans are the final objective of the research, the obvious way to do it effectively is to test humans. However, this often cannot happen as there may not be enough human volunteers coming forward, or the tests would be considered too unethical to try with a human because of the suffering they would cause.

The traditional solution to this problem was to use non-human animals instead because laws do not protect them as they protect humans (so scientists can get away with undertaking unethical experiments on them), and because they can be bred in captivity in great numbers, providing an almost endless supply of test subjects. However, for that to work, there is a big assumption that has been traditionally made, but we now know it is wrong: that non-human animals are good models of humans.

We, humans, are animals, so scientists in the past assumed that testing things in other animals would produce similar results to testing them in humans. In other words, they assume that mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, and monkeys are good models of humans, so they use them instead.

Using a model means simplifying the system, but using a non-human animal as a model of a human makes the wrong assumption because it treats them as simplifications of humans. They are not. They are different organisms altogether. As complex as we are, but different from us, so their complexity does not go necessarily in the same direction as ours.

Non-human animals are wrongly used as models of humans by the vivisection industry but they would better be described as proxies that represent us in labs, even if they are nothing like us. This is the problem because using a proxy to test how something will affect us is a methodological mistake. It’s a design error, as wrong as using dolls to vote in elections instead of citizens or using children as frontline soldiers in war. That’s why most drugs and treatments do not work. People assume that this is because science has not advanced enough. The truth is that, by using proxies as models, science is going in the wrong direction, so each advancement takes us further from our destination.

Each species of animal is different, and the differences are big enough to make any species unsuitable to be used as a model of humans we can rely on for biomedical research — which has the highest requirements of scientific rigour because mistakes cost lives. The evidence is there to be seen.

Animal experiments do not reliably predict human outcomes. The National Institutes of Health acknowledges that over 90 % of drugs that successfully pass animal tests fail or cause harm to people during human clinical trials. In 2004, the pharmaceutical company Pfizer reported that it had wasted more than $2 billion over the past decade on drugs that “failed in advanced human testing or, in a few instances, were forced off the market because of causing liver toxicity problems.” According to a 2020 study, more than 6000 putative medicines were in preclinical development, using millions of animals at an annual total cost of $11.3bn, but of these medicines, about 30% progressed to Phase I clinical trials, and only 56 (less than 1%) made it to market.

Also, reliance on animal experimentation can impede and delay scientific discovery as drugs and procedures that could be effective in humans may never be further developed because they did not pass the test with the non-human animals chosen to test them.

The failure of the animal model in medical and safety research has been known for many years now, and this is why the Three Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement) have been part of the policies of many countries. These were developed over 50 years ago by the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW) providing a framework for performing more “humane” animal research, based on doing fewer tests on animals (reduction), reducing the suffering they cause (refinement), and replacing them with non-animal tests (replacement). Although these policies recognise that we have to move away from the animal model in general, they fell short of delivering meaningful changes, and this is why vivisection is still very common and more animals than ever are suffering from it.

Some experiments and tests on animals are not necessary, so a good alternative to them is not doing them at all. There are many experiments that scientists could come up with involving humans, but they would never do them as they would be unethical, so the academic institutions they work under—which often have ethical committees — would reject them. The same should happen with any experiment involving other sentient beings other than humans.

For instance, testing tobacco should no longer happen, because tobacco use should be banned anyway, as we know how harmful is to humans. On 14th March 2024, the New South Wales Parliament, Australia, banned forced smoke inhalation and forced swim tests (used to induce depression in mice to test anti-depressant drugs), in what is believed to be the first ban of these cruel and pointless animal experiments in the world.

Then we have the research that is not experimental, but observational. The study of animal behaviour is a good example. There used to be two main schools that studied this: the American school normally composed of psychologists and the European school mainly composed of Ethologists (I am an Ethologist, belonging to this school). The former used to conduct experiments with captive animals by putting them in several situations and recording the behaviour they reacted with, while the latter would just observe the animals in the wild and not interfere at all with their lives. This non-intrusive observational research is what should replace all experimental research that not only can cause distress to the animals but is likely to produce worse results, as animals in captivity do not behave naturally. This would work for zoological, ecological, and ethological research.

Then we have experiments that can be done on volunteer humans under rigorous ethical scrutiny, using new technologies that have eliminated the need for operations (such as the use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging or MRI). A method called “microdosing” can also provide information on the safety of an experimental drug and how it is metabolised in humans before large-scale human trials.

However, in the case of most biomedical research, and the testing of products to see how safe they are for humans, we need to create new alternative methods that keep the experiments and tests but remove the non-human animals from the equation. These are what we call New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), and once developed, not only can be far more effective than animal tests but also cheaper to use (once all the developing costs have been offset) because breeding animals and keeping them alive for testing is costly. These technologies use human cells, tissues or samples in several ways. They can be used in almost any area of biomedical research, ranging from the study of disease mechanisms to drug development. NAMs are more ethical than animal experiments and provide human-relevant results with methods that are often cheaper, faster and more reliable. These technologies are poised to accelerate our transition to animal-free science, creating human-relevant results.

There are three main types of NAMs, human cell culture, organs-on-chips, and computer-based technologies, and we will be discussing them in the next chapters.

Human Cell Culture

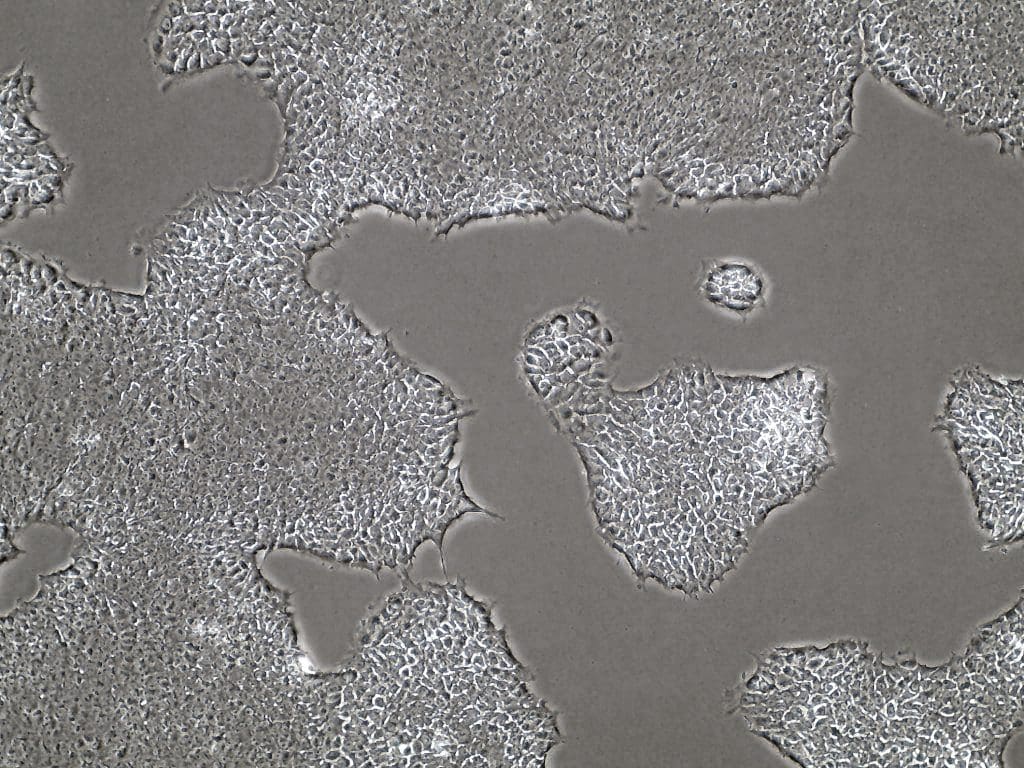

Growing human cells in culture is a well-established in vitro (in glass) research method. Experiments can use human cells and tissues donated from patients, grown as lab-cultured tissue or produced from stem cells.

One of the most important scientific advances that made the development of many NAMs possible was the ability to manipulate stem cells. Stem cells are undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells in multicellular organisms that can change into various types of cells and proliferate indefinitely to produce more of the same stem cell, so when scientists started mastering how to make human stem cells become cells from any human tissue, that was a game changer. Initially, they obtained them from human embryos before they developed into foetuses (all embryonic cells are initially stem cells), but later, scientists managed to develop them from somatic cells (any other cell of the body) which, with a process called hiPSC reprogramming, could be converted in stem cells, and then in other cells. This meant that you could get many more stem cells using ethical methods nobody would object to (as there is no need to use embryos anymore), and transform them into different types of human cells that you can then test.

Cells can be grown as flat layers in plastic dishes (2D cell culture), or 3D cell balls known as spheroids (simple 3D cell balls), or their more complex counterparts, organoids (“mini-organs”). Cell culture methods have grown in complexity over time and are now used in a wide range of research settings, including drug toxicity testing and the study of human disease mechanisms.

In 2022, researchers in Russia developed a new nanomedicine testing system based on plant leaves. Based on a spinach leaf, this system uses the leaf’s vascular structure with all cell bodies removed, apart from their walls, to imitate the arterioles and capillaries of the human brain. Human cells can be put in this scaffolding, and then drugs can be tested on them. Scientists of the ITMO University’s SCAMT Institute in St. Petersburg published their study in Nano Letters. They said that both traditional and nano-pharmaceutical treatments can be tested with this plant-based model, and they have already used it to simulate and treat thrombosis.

Professor Chris Denning and his team at the University of Nottingham in the UK are working to develop cutting-edge human stem cell models, deepening our understanding of cardiac fibrosis (thickening of the heart tissue). Because the hearts of non-human animals are very different to those of humans (for instance, if we are talking about mice or rats they have to beat much faster), animal research has been poor predictors of cardiac fibrosis in humans. Funded by Animal Free Research UK, the “Mini Hearts” Research Project led by Professor Denning is looking to deepen our understanding of cardiac fibrosis by using human stem cell 2D and 3D models to support drug discovery. So far, it has outperformed animal tests of drugs given to the team by pharmaceutical industries that wanted to check how good these NAMs are.

Another example is MatTek Life Sciences’ EpiDerm™ Tissue Model, which is a 3D human cell-derived model used to replace experiments in rabbits to test chemicals for their ability to corrode or irritate the skin. Also, the company VITROCELL produces devices used to expose human lung cells in a dish to chemicals to test the health effects of inhaled substances.

Microphysiological Systems

Microphysiological systems (MPS) is an umbrella term that includes different types of high-tech devices, such as organoids, tumoroids, and organs-on-a-chip. Organoids are grown from human stem cells to create 3D tissue in a dish that imitates human organs. Tumoroids are similar devices, but they imitate cancer tumours. Organs-on-a-chip are plastic blocks lined with human stem cells and a circuit that stimulates how organs function.

Organ-on-Chip (OoC) was selected as one of the top ten emerging technologies by The World Economic Forum in 2016. They are small plastic microfluidic chips made of a network of microchannels which connect chambers containing human cells or samples. Minute volumes of a solution can be passed through the channels with controllable speed and force, helping to mimic the conditions found in the human body. Although they are much simpler than native tissues and organs, scientists have discovered that these systems can be effective in mimicking human physiology and disease.

Individual chips can be connected to create a complex MPS (or “body-on-chips”), which can be used to study the effects of a drug on multiple organs. Organ-on-chip technology can replace animal experiments in the testing of drugs and chemical compounds, disease modelling, modelling of the blood-brain barrier and the study of single-organ function, providing complex human-relevant results. This relatively new technology is being constantly developed and refined and is set to offer a wealth of animal-free research opportunities in the future.

Research has shown some tumoroids are about 80% predictive of how effective an anti-cancer drug will be, compared with the average 8% accuracy rate in animal models.

The first World Summit on MPS was held at the end of May 2022 in New Orleans, indicating how much this new field is growing. The US FDA is already using its labs to explore these technologies, and the US National Institutes of Health has been working for ten years on tissue chips.

Companies such as AlveoliX, MIMETAS, and Emulate, Inc., have commercialised these chips so other researchers can use them.

Computer-Based Technologies

With the recent advancements of AI (Artificial Intelligence) it is expected that many animal tests will not be necessary anymore because computers could be used to test models of physiological systems and predict how new drugs or substances would affect people.

Computer-based, or in silico, technologies have grown over the past few decades, with huge advances and growth in the use of “-omics” technologies (an umbrella term for a range of computer-based analyses, such as genomics, proteomics and metabolomics, which can be used to answer both highly specific and broader research questions) and bioinformatics, combined with the more recent additions of machine learning and AI.

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes (an organism’s complete set of DNA). Proteomics is the large-scale study of proteins. Metabolomics is the scientific study of chemical processes involving metabolites, the small molecule substrates, intermediates, and products of cell metabolism.

According to Animal Free Research UK, due to the wealth of applications “-omics” could be used for, the global market for genomics alone is estimated to grow by £10.75bn between 2021-2025. Analysis of large and complex datasets provides opportunities to create personalised medicine based on an individual’s unique genetic makeup. Drugs can now be designed using computers, and mathematical models and AI can be used to predict human responses to drugs, replacing the use of animal experiments during drug development.

There is a software known as Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) that is used to predict the receptor binding site for a potential drug molecule, identifying probable binding sites and therefore avoiding testing of unwanted chemicals having no biological activity. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD) are the two general types of CADD approaches in existence.

Quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSARs) are computer-based techniques that can replace animal tests by making estimates of a substance’s likelihood of being hazardous, based on its similarity to existing substances and our knowledge of human biology.

There already have been recent scientific advances using AI to learn how proteins fold, which is a very difficult problem biochemists have been struggling with for a long time. They knew which amino acids the proteins had, and in which order, but in many cases, they did not know which 3D structure they would create in the protein, which dictates how the protein would function in the real biological world. Being able to predict which shape a new drug made of proteins will have may give an important insight into how it would react with human tissue.

Robotics can also play a role in this. Computerised human-patient simulators that behave like humans have been shown to teach students physiology and pharmacology better than vivisection.

Advances in the International Anti-Vivisection Movement

There has been progress in some countries on the replacement of animal experiments and tests. In 2022, California’s Governor Gavin Newsom signed a bill that from 1st January 2023 banned the testing of harmful chemicals on dogs and cats. California became the first state in the US to prevent companies from using companion animals to ascertain their products’ harmful effects (such as pesticides and food additives).

California passed the bill AB 357 which amends existing animal testing laws to expand the list of non-animal alternatives that some chemical testing laboratories require. The new amendment will ensure more animal tests for products such as pesticides, household products, and industrial chemicals are replaced with non-animal tests, hopefully helping to reduce the overall number of animals used each year. The bill, sponsored by the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and authored by Assemblymember Brian Maienschein, D-San Diego, was signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom on 8th October 2023.

This year, US President Joe Biden signed into law the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which ended a federal mandate that experimental drugs must be tested on animals before they are used on humans in clinical trials. This law makes it easier for drug companies to use alternative methods to animal testing. The same year, Washington State became the 12th US state to ban the sale of cosmetics newly tested on animals.

After a long process and some delays, Canada finally banned the use of animal testing for cosmetic products. On 22nd June 2023, the government made amendments to the Budget Implementation Act (Bill C-47) prohibiting these tests.

In 2022, the Dutch Parliament passed eight motions to take steps to reduce the number of animal experiments in the Netherlands. In 2016, the Dutch government pledged to develop a plan to phase out animal experiments, but it failed to meet that objective. In June 2022, the Dutch Parliament had to step in to force the government to act.

Horrific drowning and electroshock tests on countless animals will no longer be conducted in Taiwan by companies wanting to make anti-fatigue marketing claims that consuming their food or beverage products may help consumers be less tired after exercising.

In 2022, two of the largest food companies in Asia, Swire Coca-Cola Taiwan and Uni-President, announced that they were stopping all animal tests not explicitly required by law. Another important Asian company, the probiotic drinks brand Yakult Co. Ltd, also did so as its parent company, Yakult Honsha Co., Ltd., already banned such animal experiments.

In 2023, the European Commission said it would accelerate its efforts to phase out animal testing in the EU in response to a proposal by the European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI). The coalition “Save Cruelty-free Cosmetics – Commit to a Europe without Animal Testing”, suggested actions that could be taken to further reduce animal testing, which was welcomed by the Commission.

In the UK, the law that covers the use of animals in experiments and testing is the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 Amendment Regulations 2012, known as ASPA. This came into force on 1st January 2013 after the original 1986 Act was revised to include new regulations specified by the European Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Under this law, The process of obtaining a project licence includes researchers defining the level of suffering animals are likely to experience in each experiment. However, severity assessments only acknowledge the suffering caused to an animal during an experiment, and it does not include other harms animals experience during their lives in a laboratory (such as their lack of mobility, relatively barren environment, and lack of opportunities to express their instincts). According to ASPA, a “protected animal” is any living non-human vertebrate and any living cephalopod (octopuses, squid, etc.), but this term does not mean that they are protected from being used in research, but rather their use is regulated under ASPA (other animals such as insects are not afforded any legal protection). The good thing is that ASPA 2012 has enshrined the concept of the development of “alternatives” as a legal requirement, stating that “The Secretary of State must support the development and validation of alternative strategies.”

Herbie’s Law, the Next Big Thing for Animals in Labs

The UK is a country with lots of vivisection, but it is also a country with a strong opposition to animal experiments. In there, the anti-vivisection movement is not only old but also strong. The National Anti-Vivisection Society was the world’s first anti-vivisection organisation, founded in 1875 in the UK by Frances Power Cobbe. She left a few years later and in 1898 founded the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV). These organisations still exist today, with the former being part of the Animal Defenders International group, and the latter being renamed Cruelty Free International.

Another anti-vivisection organisation that changed its name was the Dr Hadwen Trust for Humane Research, founded in 1970 when BUAV set it up in honour of its former president, Dr Walter Hadwen. It initially was a grant-giving trust that awards grants to scientists to help replace the use of animals in medical research. It split from the BUAV in 1980, and in 2013 it became an incorporated charity. In April 2017, it adopted the working name Animal Free Research UK, and although it continues to provide grants to scientists, it now also runs campaigns and lobbies the government.

I am one of its supporters because they are veganising biomedical research, and a few days ago I was invited to attend a fundraising event called “A Cup of Compassion” at the Pharmacy, an excellent vegan restaurant in London, where they unveiled their new campaign: Herbie’s Law. Carla Owen, CEO of Animal Free Research UK, told me the following about it:

“Herbie’s Law represents a bold step towards a brighter future for humans and animals. Outdated animal experiments are failing us, with over 92 per cent of drugs that show promise in animal tests failing to reach the clinic and benefit patients. That’s why we need to have the courage to say ‘enough is enough’, and take action to replace animal-based research with cutting-edge, human-based methods that will deliver the medical progress we so urgently need while sparing animals from suffering.

Herbie’s Law will make this vision a reality by setting 2035 as the target year for animal experiments to be replaced with humane, effective alternatives. It will get this vital commitment onto the statute books and hold the Government to account by describing how they must kickstart and maintain progress.

At the heart of this vital new law is Herbie, a beautiful beagle who was bred for research but thankfully deemed not to be needed. He now lives happily with me and our family, but reminds us of all those animals who haven’t been as fortunate. We will be working tirelessly over the coming months to urge policymakers to introduce Herbie’s Law – a vital commitment to progress, to compassion, to a brighter future for all.”

Specifically, Herbie’s Law sets a target year for the long-term replacement of animal experiments, describes activities that the government must take to make sure that this happens (including publishing action plans and progress reports to Parliament), establishes an Expert Advisory Committee, develops financial incentives and research grants for the creation of human-specific technologies, and provides transition support for scientists/orgs to move from animal use to human-specific technologies.

One of the things I like the most about Animal Free Research UK is that they are not about the three Rs, but only about one of the Rs, the “Replacement”. They do not advocate for the reduction of animal experiments, or their refinement to reduce suffering, but their complete abolition and replacement with animal-free alternatives — they are, therefore, abolitionists, like me. Dr Gemma Davies, Science Communications Officer of the organisation, told me this about their position regarding the 3Rs:

“At Animal Free Research UK, our focus is, and has always been, the end of animal experiments in medical research. We believe that experiments on animals are scientifically and ethically unjustifiable, and that championing pioneering animal-free research provides the best chance of finding treatments for human diseases. Therefore, we do not endorse the principles of the 3Rs and are instead fully committed to the replacement of animal experiments with innovative, human-relevant technologies.

In 2022, 2.76 million scientific procedures using live animals were carried out in the UK, 96% of which used mice, rats, birds or fish. Although the 3Rs principles encourage Replacement where possible, the number of animals used was only a 10% decrease compared to 2021. We believe that under the framework of the 3Rs, progress is simply not being made fast enough. The principles of Reduction and Refinement often distract from the overall goal of Replacement, allowing the unnecessary reliance on animal experiments to continue. Over the next decade, we want the UK to lead the way in moving away from the 3Rs concept, establishing Herbie’s Law to shift our focus towards human-relevant technologies, enabling us to finally remove animals from laboratories altogether.”

I think this is the right approach, and the proof that they mean it is that they set up a deadline of 2035, and they aim at Herbie’s Law, not Herbie’s policy, to make sure politicians deliver on what they promise (if they pass it, of course). I think setting a 10-year target for an actual law that forces the government and corporations to act can be more effective than setting a 5-year target that only leads to a policy, as policies often end up watered down and not always followed. I asked Carla why precisely 2035, and she said the following:

“Recent advances in new approach methodologies (NAMs) such as organ-on-chip and computer-based approaches give hope that change is on the horizon, however, we are not quite there yet. While there is no requirement for animal experiments to be carried out in basic research, international regulatory guidelines during drug development mean that countless animal experiments are still carried out each year. While we as a charity want to see the end of animal experiments as quickly as possible, we understand that such a significant shift in direction, mindset and regulations takes time. Appropriate validation and optimisation of new animal-free methods must take place to not only prove and showcase the opportunities and versatility provided by NAMs but to also build trust and remove bias against research that moves away from the current ‘gold standard’ of animal experiments.

However, there is hope, because as more pioneering scientists utilise NAMs to publish ground-breaking, human-focussed experimental results in high-calibre scientific journals, confidence will grow in their relevance and effectiveness over animal experiments. Outside of academia, the uptake of NAMs by pharmaceutical companies during drug development will be a crucial step forward. Whilst this is something which is slowly beginning to happen, the full replacement of animal experiments by pharmaceutical companies is likely to be a key turning point in this effort. After all, using human cells, tissues and biomaterials in research can tell us more about human diseases than any animal experiment ever could. Building confidence in new technologies across all areas of research will contribute to their wider uptake over the coming years, eventually making NAMs the obvious and first choice.

Although we expect to see significant progress milestones along the way, we have chosen 2035 as the target year to replace animal experiments. By working closely with scientists, parliamentarians, academics and industry, we are pushing towards a “decade of change”. While this may feel a long way off to some, this time is needed to provide ample opportunity for academia, research industries and the published scientific literature to fully reflect the benefits and opportunities provided by NAMs, in turn building the wider scientific community’s confidence and trust across all areas of research. These relatively new tools are being constantly developed and refined, positioning us to make incredible breakthroughs in human-relevant science without the use of animals. This promises to be an exciting decade of innovation and progress, moving closer each day to our goal of ending animal experiments in medical research.

We are asking scientists to change their methods, embrace opportunities to retrain and alter their mindsets to prioritise innovative, human-relevant technologies. Together we can move towards a brighter future for not only the patients who desperately need new and effective treatments but also for the animals who would otherwise be destined to suffer through unnecessary experiments.”

All this is hopeful. Forgetting the two first Rs by focusing on Replacement alone and setting a target not too distant in the future for complete abolition (not percentual reformist targets) seems the right approach to me. One that finally could break the stalemate we and the other animals have been stuck with for decades.

I think Herbie and the Battersea brown dog would have been very good friends.

Notice: This content was initially published on VeganFTA.com and may not necessarily reflect the views of the Humane Foundation.